The Triassic period

The lagoon of Monte San Giorgio

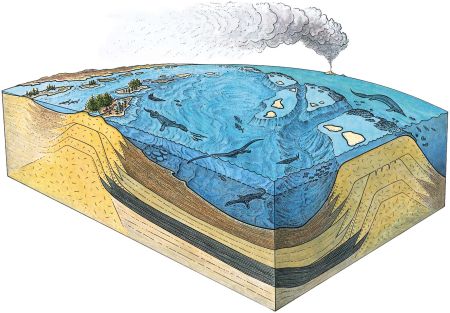

During the Middle Triassic (247–235 millions years ago) Monte San Giorgio was not the mountain we know today, but the bottom of a shallow sea located at the western margin of the Tethys. The environment was characterized by the presence of small islands and banks of fine sand. These separated the coast from the open sea, forming a lagoon or a more or less isolated basin. The landscape was similar to that of the modern-day Bahamas or Maldives: an archipelago of small islands and carbonate platforms, not too distant from active volcanoes. However, the large submerged carbonate structures of Monte San Giorgio were not formed by reef-building corals as they are today (which in the Middle Triassic were rare) but by other organisms, such as calcareous algae of the genus Diplopora.

Thin section of the calacareous algae Diplopora from the San Salvatore Dolomite (image width 8 mm), © MCSN Picture R. Stockar

In these calm and shallow waters less than 100 m deep, and under a subtropical climate, a rich marine fauna developed comprising different groups of invertebrates (molluscs, brachiopods, crustaceans, echinoderms), conodonts (an extinct group similar to modern lampreys), cartilaginous and bony fishes, and many reptiles adapted to either an aquatic or amphibious life. The coast was relatively nearby and covered by a vegetation of tree ferns, conifers and other primitive plants, which was populated by numerous animals from small insects to large reptiles.

When they died, the marine organisms (and some of the terrestrial organisms transported into the sea by wind, rivers or waves) were deposited at the bottom of the basin. Due to the poor water circulation the decomposition processes resulted in the consumption of all of the oxygen available. A layer of fine blackish mud with practically no life was formed, which gradually swallowed up the remains of the different organisms. In this way, the animal and plant remains escaped their natural fate of being dismembered and consumed by communities at the seabed, which could not survive in such conditions.

Over time, their remains were increasingly compressed within the mass of mud by the weight of still accumulating sediments above, allowing their fossilization down to the finest details. Today, such deposits of dark, organic-rich material are named “oil” or “bituminous” shales; at Monte San Giorgio they are the richest rocks in terms of fossil content.

Schematic representation of the ecosystem and sedimentary environment at the time of the deposition of the lower Meride Limestone, ca. 240 millions years ago. (Illustration H. Furrer / B. Scheffold 1999)