Quarries and mines

“Oil shale” mines

The bituminous shales of Monte San Giorgio have been exploited in mines above Besano since the first half of the 18th century. In 1830, studies were conducted on gas production from these shales for the street lightning of Milan, but this and other projects were quickly shelved. In 1861 Ticino’s government allowed several mines to open in the territories of Meride and Brusino, but these exploitation attempts also did not last very long.

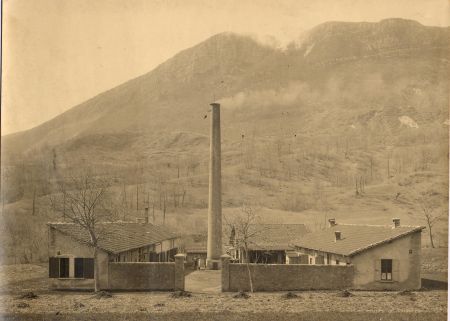

In 1906, mining was re-established at Monte San Giorgio in an old gallery above Tre Fontane near Serpiano. In 1910, the newly founded Società Anonima Miniere Scisti Bituminosi di Meride e Besano, opened a factory for the production of oil in Spinirolo near Meride. This followed the commercial success of “Ichthyol” extracted from similar bituminous shale from the Upper Triassic of Seefeld in Tirol (Austria). The oil was produced by a dry distillation of the bituminous shale then refined to form an oil or ointment called “Saurolo”, very similar to “Ichthyol”, and sold by the pharmaceutical industries of Basel and Milano to treat skin disease.

The old oil factory in Spinirolo near Meride at around 1940, © FMSG / Sommaruga archive

Packaging of the medicinal ointment “Saurolo” from the company Adroka (Basel), © Adroka / PIMUZ archive

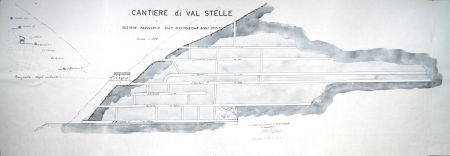

In 1916, five tunnels totalling 900m in length were in use in Tre Fontane, and had by then supplied an estimated 2100 tons of useful material. By 1940 the galleries were expanded to about 1770m. From 1917 to 1927 another site in Val Porina was also exploited. In 1922 mining resumed in the Selva Bella mine above Besano, and some years later, the Novella oil factory in Besano started processing the raw material.

Map of the Tre Fontane mine (Val di Stelle), in an application for exploitation from 1943, © Landesgeologie archive, swisstopo

The entrance of the Tre Fontane mine with the miners’ house at around 1916, © FMSG / Sommaruga archive

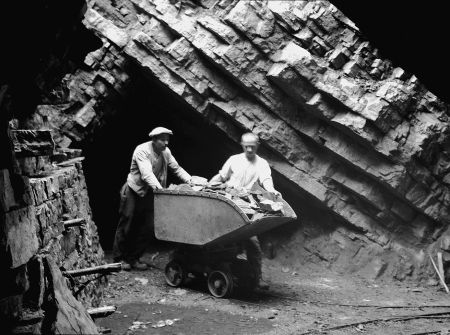

Miner in the gallery of the Tre Fontane mine at around 1916, © FMSG / Sommaruga archive

Two miners at the gallery entrance of the ancient mine in Val Porina at around 1931, © PIMUZ / B. Peyer

Bituminous shales were mined from the middle part of the Besano Formation (formerly the “Grenzbitumenzone”). Their content of organic carbon lies between 20-44% of the total weight; the yield was 74-85 liters of crude oil per ton of raw material. The dry distillation at low temperature, however, not only provided 8% of the weight of the material in crude oil with sulfur content of 7%, but also 8-9% of gas and 2-3% ammonia. The average production of bituminous shale fluctuated between 300 and 400 tons per year, from which 22-30 tons of crude oil were extracted. Because of export difficulties, the production declined during the Second World War, but there was a later small boom that lasted for a few years. At that time, 30 people (miners and others) were employed by the mining company. The exploitation of bituminous shale stopped in 1950, and in 1954 the production and distribution of “Saurolo” also ceased.

Galena, barite, and fluorite mines

Galena, barite, and fluorite all occur on Monte San Giorgio along tectonic faults and dykes, embedded in the volcanic rocks of the Permian and in the overlying Lower and Middle Triassic sediments. The deposits were enriched during the Middle Triassic by hydrothermal fluids moving along tectonic faults. The exploitation of a silver-galena mine in Rio Vallone, south of Porto Ceresio, was important from the first half of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century. Ore minerals are concentrated along a tectonic fault, which separates the Permian volcanics from the Lower Triassic Servino rocks. Concentrations of barite and fluorite were exploited from dykes in the Permian volcanics on Monte Grumello, east of Porto Ceresio. Another dyke of barite in the Permian volcanics was exploited from 1942 to 1944 near the Hotel Serpiano. Barium sulfate was used as a raw material in metallurgy and in the colour industry.

Gypsum quarries

Three gypsum lenses in the Pizzella Marl were exploited in the surroundings of Meride from the 19th century until 1939. The extracted material was processed in the gypsum mill of La Guana. Lenses of gypsum intercalated with marls and dolomite were formed at the end of the Middle Triassic, when there was a phase of emersion followed by the development of shallow marine areas and extensive coastal zones.

“Marble” quarries

The oldest historical records of building stone from the Monte San Giorgio area date from the 16th century. They document the operations of quarries in Viggiù and Saltrio on the southern flank of Monte Orsa in Italian territory, as well as in the triangle between Arzo-Tremona-Besazio on the Swiss side. The Arzo quarries were already well known at the time of the Renaissance. The rocks of Viggiù, including the various types of “Marmo di Arzo” (Arzo marble), from the Lower Jurassic were not only used locally but also throughout Europe. Due to their rich colours they have been incorporated into Baroque churches. The three most important rock types, “Macchia Vecchia”, “Broccatello”, and “Rosso d’Arzo”, were skillfully processed into baptismal fonts, christening fonts, balustrades, columns, floors, and stairs. They also decorate altars, such as those in the domes of Como and Milano as well as the monastery of Einsiedeln in Northern Switzerland.

Processing and trading of building stone from Monte San Giorgio was most wide-spread in the Baroque (17th century) and Neoclassical (18th century) periods, and to a lesser extent in the 19th century. Despite the economic crisis of the early 20th century and other unfavorable factors (such as the production of concrete), quarrying of building stone was an important source of income until the mid-20th century. In 1931, approximately 50 small firms with 240 employees were active in Viggiù, a village with a total of 2400 habitants. Saltrio had 16 factories at that time and Arzo had 6. The quarrying was done by small family businesses with the help of day laborers. The quarries were the property of firms (Viggiù) or were rented by the municipality (Saltrio) or the patriciate (Arzo).

Originally, quarrying was done with traditional tools such as sledge hammers, splitting wedges and chisels. The blocks were then pulled by ropes and moved on wooden rollers. Often the whole family had to participate in the work at the quarry and factory. Around 1925, a new sawing technique was introduced: a helicoidal steel wire driven by a motor cut the stone from the rocky wall using the abrasive action of quartz sand. This process became even more efficient when it was modified to use a wire covered by industrial diamonds. Other aspects of processing were also mechanized with the introduction of diamond stone saws and grinding machines. Unfortunately, in 2010, the last two quarries in Arzo were closed.